Oliver Hearth Tax Record

In 1662 parliament accepted that King Charles II required an annual income of £1.2 million to run the country.

In 1661 there had been a £300,000 shortfall, a shortfall that the new hearth tax, introduced in 1662, was predicted to meet.

Sometimes referred to as 'chimney money', the hearth tax was a property tax and was graded according to the number of fireplaces in a dwelling.

The 1662 Act introducing the tax stated that 'every dwelling and other House and Edifice ... shall be chargeable ... for every firehearth and stove ... the sum of twoe shillings by the yeare'.

The money was to be paid in two equal instalments at Michaelmas (29 September) and Lady Day (25 March).

The 1662 Act also specified that certain hearths would not be liable for the tax including those in houses already exempt from paying local taxes to the church and the poor due to 'poverty or smallness of estate'.

At no time during its existence between 1662 and 1689 did the hearth ever tax yield its expected target of £300,000 per annum. The first two collections raised only £115,000 and by 1666 the annual net yield had fallen to about £103,000. Subsequent changes in management and collection saw a gradual increase in annual yield to about £157,000 in 1670 and in 1680 it reached its highest yield of £216,000.

Finally the tax was repealed in 1689 at the start of King William and Queen Mary's reign in order to gain popularity.

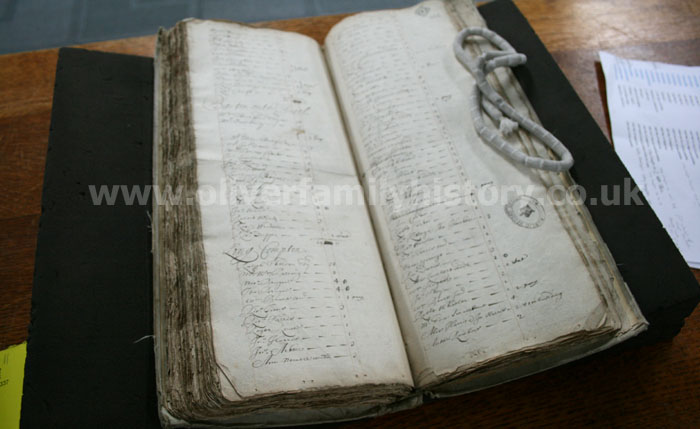

Many records from the hearth tax administration remain in archives today including those for Long Compton from the early 1670's.

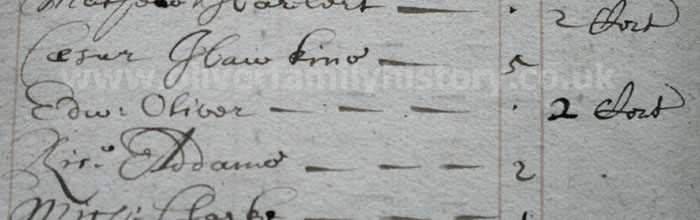

Browsing the Long Compton lists we're fortunate to find a record for an Edward Oliver, this is almost certainly Edward, father of Josiah, so therein our direct ancestor.

The record details that Edwards property had 2 hearths however the number is written outside of the main recording column which may denote that Edward was exempt from the tax. Unfortunately the instructions for recording exemptions were not standardised across the country leading to hearth tax officials employing their own methods from place to place.

Regardless, the survival of these records are just fabulous in that they allow a small little window into the economic and social status of what are our earliest, direct, Oliver ancestors traced to date - hard black and white evidence from almost 350 years ago, wow.

Photographs taken at the Warwickshire Records Office.

Oliver Family History

Stories

1600 - 1699

- Oliver Hearth Tax record

- First Oliver marriage in Oxfordshire

1700 - 1799

- Oliver found in 1762 Rectors book

- Stonesfield & Finstock Oliver's

1800 - 1899

- Methodism comes to Stonesfield

- Oliver's discover dinosaurs?

- An Oliver Waterloo veteran

- James Oliver Army Discharge Papers

- Solomon and Joshua - Banished!

- Lost to a tragic maritime disaster

- The Welsh connection

- Oliver prisoner portrait

- Oliver's found playing cricket

- Fantastic Oliver family photograph

- Workhouse lives

- Stonesfield turns on the waterworks

1900 - Current Day

- Built by Olivers in Oak Bay,Canada

- A 100 year old cricket medal

- The Stonesfield Friendly Society

- A WW1 hero remembered

- Oliver men on Oxford War Memorials

- Oliver Army records

- Success at the Village Fete

- Sole Survivor of H49 during WWII

- Aussie Cycling Champion

- Record Breaking Blanket Making

- Oliver Weddings through the years