Solomon and Joshua: Banished!

The life of Solomon Oliver and the stories of his descendants are some of the most interesting of all our discoveries. Though in the case of Solomon himself, simply picking up his life at the time of the early census records alone (1841/1851) would indicate nothing too exceptional.

As we know though, the key to locating really interesting family history is to move beyond the usual birth, marriage, death and census records into the more detailed and more specialised record sets and archives.

For several years now Solomon has been the topic of much debate and conversation due to some records raising as many questions as they give answers.

One episode from Solomon’s life in 1827 stands out in particular and this article focuses primarily on this, though first, we go back to a little further.

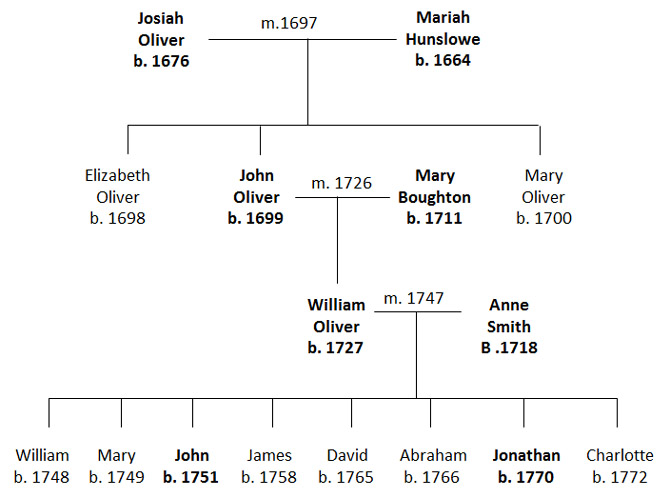

I think it’s reasonable for us not to question whether Solomon indeed descends from Josiah Oliver b.1676, more the issue is confirming through which line he descends as the parentage of Solomon is not entirely clear from the Stonesfield Parish records which include the following baptisms:

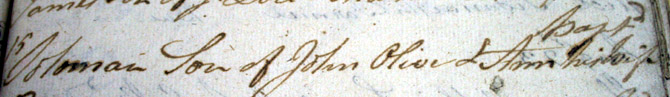

Joshua Oliver, 1797, May 21, s. John (no mother's name)

Solomon Oliver, 1802, Aug 15, s. John and Ann

and

James Oliver, 1803, Jul 24, s. Jonathan (no mother's name)

Photographs taken at the Oxfordshire Records Office

All three records indicate a father’s name of John or Jonathan and we see William (b.1727) and Ann had both a John (b. 1751) and a Jonathan (b.1770). A number of questions are raised here including are these 3 boys all sons of either John or Jonathan or perhaps they are split across them?

Whilst John’s wife Sarah gave birth to a child in 1794 when she was 44, by the time of Joshua’s birth she would have been aged 48, Solomon, 52 and James, 53, so perhaps this raises some doubts. As for Jonathan, his age fits well and James’ birth references Jonathan as the father’s name (and it wasn’t uncommon to abbreviate Jonathan to Jon, or John as a variant). With Jonathan however there is no record of a marriage in Stonesfield or indeed Oxfordshire, nor any death record for an Ann Oliver per Solomon’s baptism. Jonathan’s death is recorded in 1810 in Stonesfield.

So perhaps these are three brothers, the children of Jonathan and Ann, but sadly from the records that we have seen to date it’s impossible to be conclusive. Brothers or not, Joshua and Solomon would go on to play a significant part in one another’s lives, as this article will go on to describe.

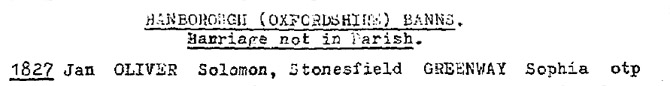

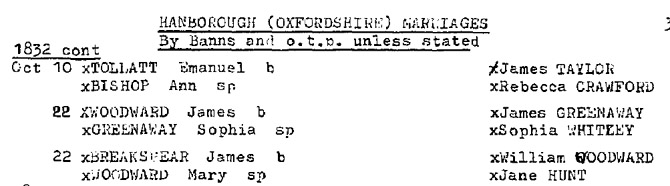

To our knowledge Solomon grew up in Stonesfield but there is no specific mention of him within the limited local and informal census records of 1811 and 1821. We next locate Solomon in January 1827 with the below entry from the Hanborough Parish Register transcripts showing Banns being read for his planned marriage to Sophia Greenway.

No doubt this would have been a happy time for both Solomon and Sophia with the imminent prospect of a new life together.

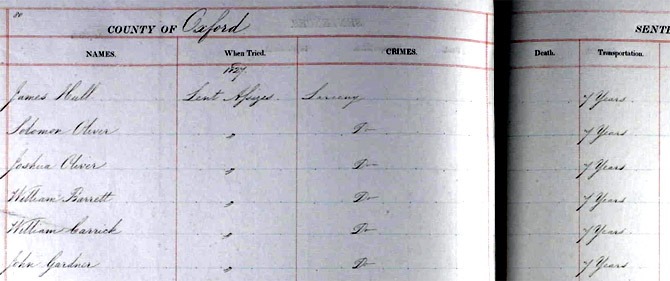

Almost immediately however the happiness would be shattered and one of the most significant episodes of Solomon’s life would begin to unfold. One of the first records to bring this to light is The Oxfordshire Criminal Register for the Lent Quarter of 1827 within which we find the following faint entries:

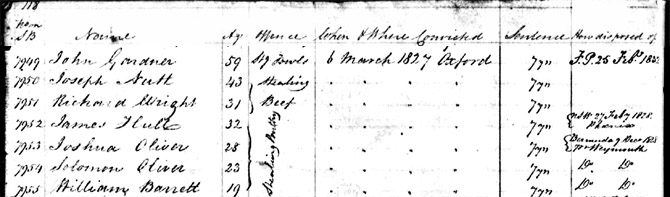

Included are:

Name: Solomon Oliver, Crimes: Larceny, Sentence: Transportation, 7 years

Name: Joshua Oliver, Crimes: Larceny, Sentence: Transportation, 7 years

Larceny!.. 7 years' transportation! … what could this all be about? Were they actually transported? Where to? Did the planned marriage to Sophia still happen?

The limited information within the Criminal Register raises many questions and therefore the need for more investigation. Through multiple sources including further crime, newspaper and transportation related archives and publications we now have a fuller picture of the crime, and its consequences.

Firstly, the crime. Below is a section of a 1797 map showing Stonesfield and its surrounding villages. Stonesfield and Fawler are highlighted, Stonesfield because this is where Solomon and Joshua lived, and Fawler because this is where the crime took place.

At the Oxford Assizes on the 6th March 1827 Solomon, Joshua and a third man William Barrett were charged with feloniously stealing from a hen house in Fawler, 4 live turkeys, the property of Thomas Padbury, of Stonesfield.

The court heard from a George Bossom, Constable, and how he saw Solomon and Joshua go into a market in Oxford on the 24th January and offer the live turkeys for sale. They were then apprehended on suspicion of stealing them.

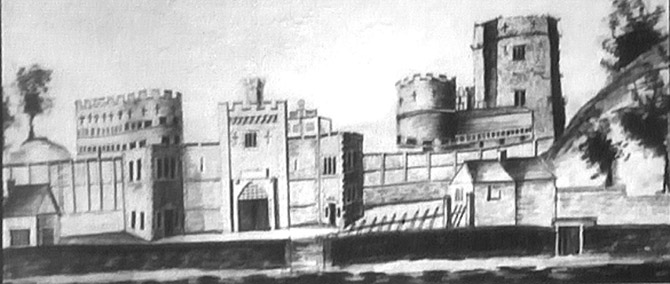

According to evidence from Thomas Padbury the turkeys disappeared between the 23rd and 24th January, within days of the above marriage banns in Hanborough. Following apprehension on January 24th they were quickly called to the magistrate’s court that then committed them to Oxford Gaol to await the assizes on the 6th March, and as mentioned above this is where they were charged.

Oxford Gaol, circa 1800

Now, the punishment.

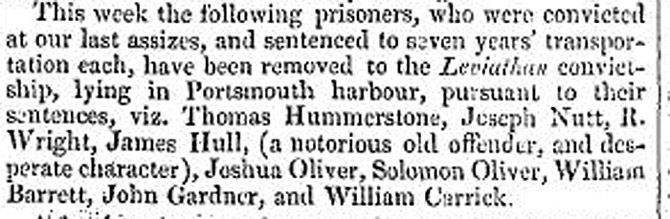

Very little detail was reported in the local newspapers but the following did appear in the March 31st edition of the Jackson’s Oxford Journal:

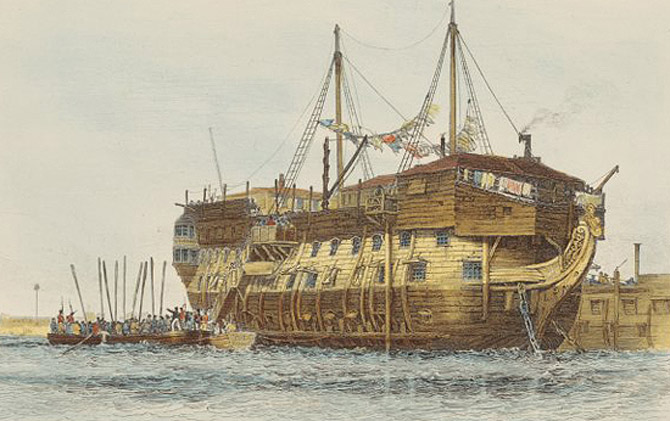

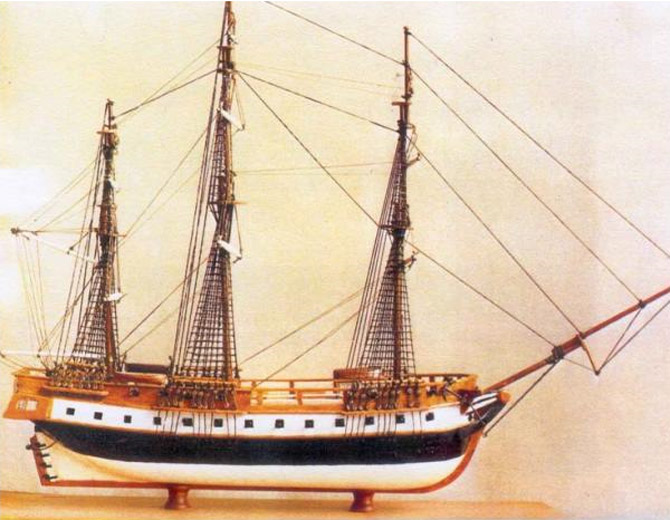

At the assize court they were charged and sentenced to 7 years’ transportation and per the above newspaper article they were ‘removed’ to the Leviathan convict ship, pending transportation. Convict ships or Prison hulks as they were also known were decommissioned naval ships and convicts were often held here, in squalid conditions, awaiting transportation. An example of such a convict ship is illustrated below:

Using the Prison Hulk Registers we are able to see that Joshua and Solomon were received on the Leviathan in Portsmouth on the 27th March 1827.

Upon arrival they would have been immediately stripped and washed, clothed in coarse grey jackets and breeches, and two irons placed on one of their legs. Whilst in Portsmouth prior to transportation the Leviathan would have been positioned out at sea and the convicts would have been rowed into land each day for work.

This register also informs us of where they were ultimately transported more than 18 months later on the convict transport ship, The Weymouth – Bermuda.

Prisoner Number: 7953, Name: Joshua Oliver, Age: 28, Offence: Stealing Poultry, When & Where Convicted: 6 March 1827 Oxford, Sentence: 7Y, How disposed of: Bermuda 9 Decr 1828 per Weymouth

Prisoner Number: 7954, Name: Solomon Oliver, Age: 23, Offence: Stealing Poultry, When & Where Convicted: 6 March 1827 Oxford, Sentence: 7Y, How disposed of: Bermuda 9 Decr 1828 per Weymouth

The Weymouth, with Solomon and Joshua on board arrived in Bermuda on the 28th February 1829, more than 2 years after the crime. The below illustrates a model of The Weymouth:

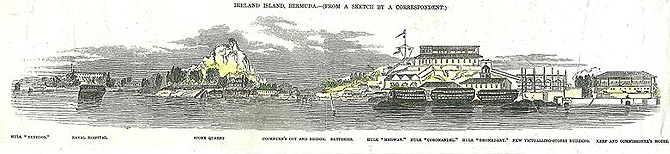

The following illustrates perhaps the first view that Solomon and Joshua would have themselves seen upon arrival at Ireland Island, Bermuda.

If we think of convict transportation in the early 1800’s our first thought might be of Australia, but many convicts were also sent to places like Gibraltar, Mauritius and Bermuda. These seemingly tropical paradises were far from this for the convicts.

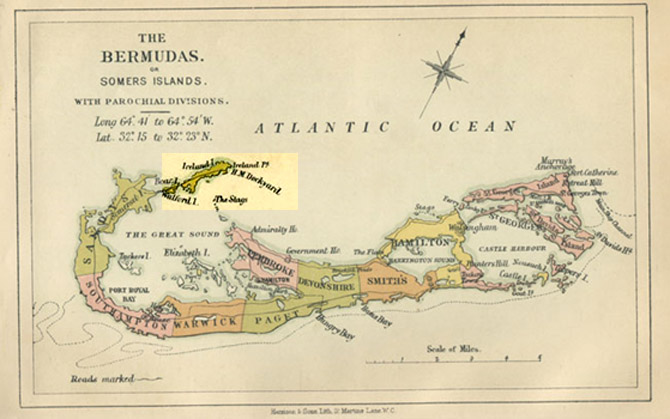

Between 1823 and 1863 more than 9000 convicts arrived in Bermuda to build the Royal Naval Dockyards at Ireland Island, highlighted on the above map. The construction started in 1809 and initially the work was done by slaves but with few slaves in Bermuda the progress was slow and a larger work force was required. An act of parliament in 1823 authorised convicts to be employed in hard labour in any colony designated by the King, and soon after this it was agreed that convicts would be used to complete the Royal Naval Dockyards in Bermuda.

The hard and heavy manual work was in hot and humid conditions and involved the breaking of hard limestone with only the most basic of implements. The first ship to arrive in Bermuda was the Antelope in 1823 bringing 300 convicts, then the Dromedary in 1826, then the Coromandel in 1827 and by the time Solomon and Joshua arrived on the Weymouth with another 300 convicts there was a workforce of more than 1000 present.

Transportation to Bermuda was considered much worse than Australia. In Australia a convict could often expect to serve only half the sentence, a convict in Bermuda was likely to see out almost all the sentence.

Detailed accounts exist of the work that took place on the Royal Naval Dockyard with the convicts ferried in each morning from the hulks in chains and made to perform the work of horses, dragging carts of heavy stone. Then each evening they would be taken back to the dirty, dimly lit hulks with little chance of free time.

Below is an image of a convict in Bermuda and the uniform they were obliged to wear, a smock including the ship name, convict number and name.

Tracking the prison hulk registers in Bermuda we find that Joshua and Solomon were moved between prison hulks again, this time to the Coromandel.

By the last quarter of 1829 the paths of Solomon and Joshua would part. We know that Solomon ultimately returned to England but the story of what happened to Joshua is more mysterious as he could not be found back in England. One possibility was that he chose to emigrate to Australia or America after transportation, maybe meaning a whole new branch of Olivers are out there to be discovered. Using further records from Bermuda we can ascertain exactly what happened to Joshua, and unfortunately it’s a rather sad story.

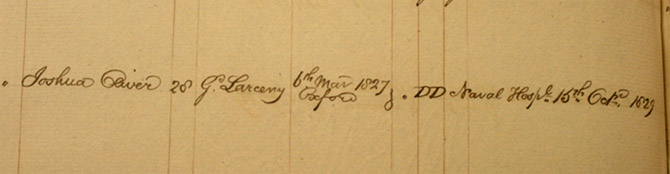

The Prison Hulk Register for the Coromandel for the last quarter of 1829 includes the following entry:

Photograph taken at the National Archives, Kew

This reads:

Name: Joshua Oliver, Age: 28, Offence: Grand Larceny, When & Where Convicted: 6 March 1827 Oxford, Bodily State: DD, Remarks: Naval Hospital, 15th October 1829

DD means Died. So this entry confirms that Joshua had been transferred to the Naval Hospital and had died there on 15th October 1829.

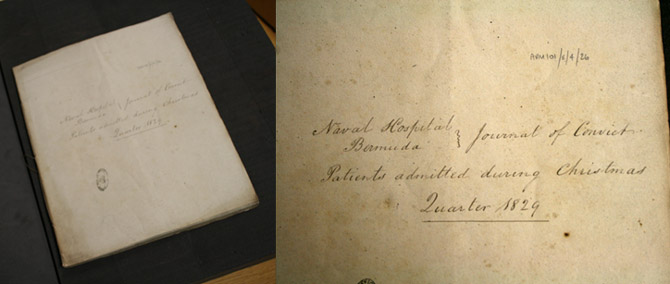

The next document to be discovered provides an incredible sense of time travel back to the bedside of Joshua as detailed records from the Naval Hospital, including specific entries regarding Joshua and the cause of his death, also still exist.

Photograph taken at the National Archives, Kew

Two detailed entries from the surgeon for Quarters 3 and 4 of 1829 can be found as follows:

Quarter 3, 1829 - Diarrhoea

'On admission the Patient complained of all the usual symptoms of Diarrhoea attended with weakness debility and broken down constitution, a complete skeleton, low fever of the typhoid character, the purging, Griping and tenesmus with unhealthy stools together with indurated mesentery Gland, the vomiting immediately which ever the patient swallowed, shewed too plainly the complaint had advanced too far to afford any prospect of advantage from Medecine - the warm Bath, Sal mixt: Dovers Powders, Weak Lin[imen]ts and the usual remedies were employed in vain.'

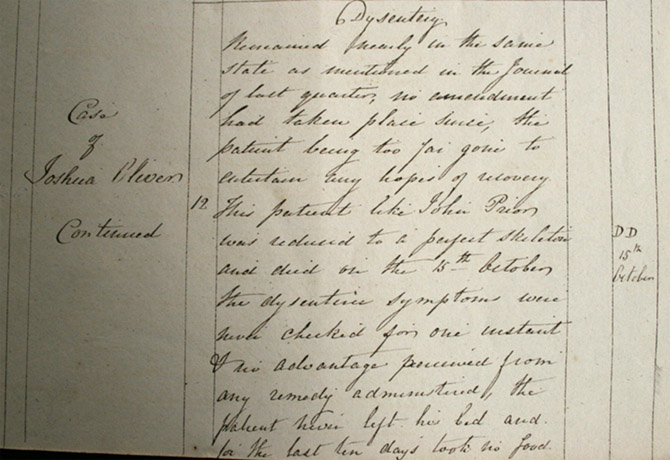

Quarter 4, 1829: Case of Joshua Oliver Continued, Dysentery

‘Remained mainly in the same state as mentioned in the Journal of last quarter, no amendment had taken place since, the patient being too far gone to entertain any hopes of recovery. This patient like John Prior was reduced to a perfect skeleton and died on the 15th October, the dysenteric symptoms were never checked for one instant & no advantage perceived from any remedy administered, the patient never left his bed and in the last ten days took no food or medicine whatever, only drink he appeared entirely worn out and exhausted from the violence of the complaint at the first’

DD 15th Oct.

Photograph taken at the National Archives, Kew

The story ends sadly and cruelly for Joshua, though it appears the surgeons at the hospital tried everything to help him recover. Having seen and held the very document that was there with Joshua at the hospital gave an amazing and moving sense of connection to that sad time in 1829.

Of the 9000 convicts that arrived in Bermuda between 1823 and 1863 some 2000 died in Bermuda and there is a convict cemetery on Ireland Island. This is where Joshua was also laid to rest. Today only 13 graves are marked and only 4 have names and the cemetery is respectfully maintained by the National Trust of Bermuda.

We can only imagine how tough this must have been for Solomon to witness what may well be his brother decline and ultimately succumb to the consequences of that day in January 1827.

Photographs from http://www.findagrave.com/

Solomon himself continued on the Coromandel prison hulk where his bodily condition was described as Good and his conduct was described as Very Good.

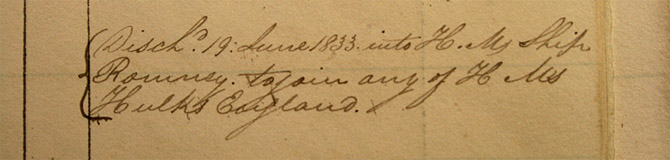

He continued to work through 1830, 1831 when he was moved to the Dromedary ship, then through 1832 and into 1833. Here we find the following entry in the Dromedary register of June 1833:

Photograph taken at the National Archives, Kew

This reads:

Discharged 19th June 1833 in HM Ship Romney to join any of HM Hulks, England.

So Solomon is to be transferred back home! By the 20th July 1833 HMS Romney is reported as back on British shores where Solomon is briefly placed onto the prison hulk Captivity, and then we find the following prison hulk entry:

Photograph taken at the National Archives, Kew

This reads:

Pardoned Aug 6 1833

So more than six years into his 7 year sentence Solomon will have found himself turned out from the prison hulk in Devonport and free again to return to his native Stonesfield. Presumably in 1833 he would have walked most of the journey, which was some 200 miles.

At this point we should cast our memories back to January 1827 and the plans of marriage to Sophia Greenway. Would Solomon be hoping Sophia had waited for him? Had Sophia waited? Potentially the prospect of returning to England to his love Sophia would have been one of the thoughts that helped him through.

This could be pure romance, but the records do seem to indicate that Sophia did wait several years for Solomon to return as it was not until 1832 that she did marry. This is almost 6 years from their planned marriage, and less than 1 year before Solomon actually returned.

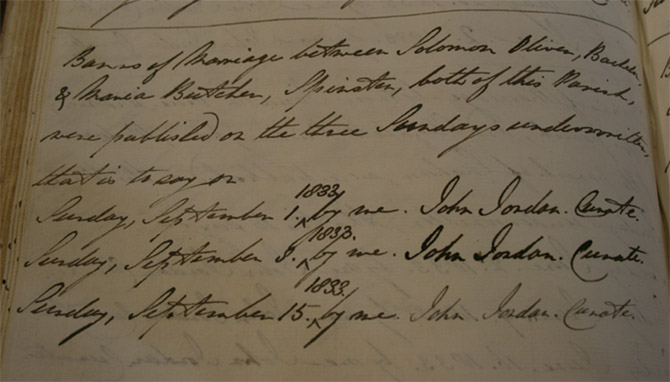

If there was heartache for Solomon regarding Sophia he was somewhat swift in moving on. Considering he was pardoned on the 6th Aug and it would have taken at least a couple of days to travel, we are soon able to find banns for a marriage to Maria Butcher being read on the 1st, 8th and 15th of September 1833 and then their marriage the very next day on the 16th September 1833.

Photograph taken at the Oxfordshire Records Office

Solomon's story includes at least one more puzzle in that 5 of his children were baptised with a mother's name of Sophia, rather than Maria:

Prudence 1834 d. Solomon and Maria

Thomas 1837 s. of Solomon and Sophia

Spencer 1839 s. of Solomon and Sophia

Albert 1841 s. of Solomon and Sophia

Urban/Herbert 1844 s. of Solomon and Sophia

Maria 1847 d. of Solomon and Sophia

No better explanation than Sophia sounding like Maria or a simple administrative error is yet to be found for this.

This story of crime and punishment ends so differently for Solomon and Joshua. Of course Solomon was lucky enough to return and continue his life, but surely the effects of that period would have been significant on him, lost love, lost family and prolonged physical and mental exhaustion.

If lessons can be learned from such an episode, or some good come from it, it appears it did in the people Solomon raised his children to be. Albert Oliver and his family, Prudence Griffin née Oliver and her family were some of the most respected people within the local communities, some holding positions of trust and authority, some exhibiting industriousness and entrepreneurialism through successful business ventures. Without doubt it would seem the life and experiences of Solomon Oliver have had a profound and complete effect of the lives of the families that have followed since.

Oliver Family History

Stories

1600 - 1699

- Oliver Hearth Tax record

- First Oliver marriage in Oxfordshire

1700 - 1799

- Oliver found in 1762 Rectors book

- Stonesfield & Finstock Oliver's

1800 - 1899

- Methodism comes to Stonesfield

- Oliver's discover dinosaurs?

- An Oliver Waterloo veteran

- James Oliver Army Discharge Papers

- Solomon and Joshua - Banished!

- Lost to a tragic maritime disaster

- The Welsh connection

- Oliver prisoner portrait

- Oliver's found playing cricket

- Fantastic Oliver family photograph

- Workhouse lives

- Stonesfield turns on the waterworks

1900 - Current Day

- Built by Olivers in Oak Bay,Canada

- A 100 year old cricket medal

- The Stonesfield Friendly Society

- A WW1 hero remembered

- Oliver men on Oxford War Memorials

- Oliver Army records

- Success at the Village Fete

- Sole Survivor of H49 during WWII

- Aussie Cycling Champion

- Record Breaking Blanket Making

- Oliver Weddings through the years